The songs convey personal attitudes, daily experiences, and conflicts; they also tell of pogroms, revolutions and wars, social and political movements, internal migrations and mass-migration to America. In Yiddish song, we hear about family relationships, local tragedies, frustrated love, seductions, suicides, and even murders. We hear the voices of children at play and of mothers singing tender lullabies; we are a part of family and wedding celebrations. There are songs which tell of accidents and of tragedies of workers at their machines; of the struggle against oppression and exploitation; of folk heroes who avenged the persecution of tyrants. Major events and minor occurrences, persons of renown and lesser figures, the shtetl and the city, are encompassed by the Yiddish song.

Although we have no records of the oldest Yiddish songs, we do know that Rabbi Jacob haLevi Moelin (Maharil), a noted rabbinic authority (1365-1427), already inveighed against the singing of a religious song in Yiddish. Secular themes penetrated the walls of the Jewish community, just as Jewish themes were borrowed by the gentile world. From rabbinic prohibitions at various times, we can assume that this cultural exchange was prevalent: gentile songs may not be used as lullabies; a Jew may not teach a Jewish melody to a gentile; secular love songs are forbidden to be sung by Jews; listening to music on the Sabbath is prohibited even when a non-Jew is playing, and so on.

Preserved manuscript collections of the texts of songs which were sung in the 15th and 16th centuries include Sabbath zmires, holiday songs, riddle and wedding songs, love songs and dances, as well as songs of satirical and didactic content. Among the last are criticism of the leaders of the Jewish community, condemnation of greed and the evils of money, gambling, warnings of the inevitability of death, disputes between wine and water and between good and evil inclinations. From the 17th and 18th centuries, songs also record historical events such as fires and plagues, as well as the expulsions of Jewish communities; there are lamentations over pogroms in various communities and the Khmelnytzky massacres in the Ukraine; and there is a song about Shabbetai Zevi and his pseudo-Messianic movement. All these are augmented by the continuous didactic and holiday motifs.

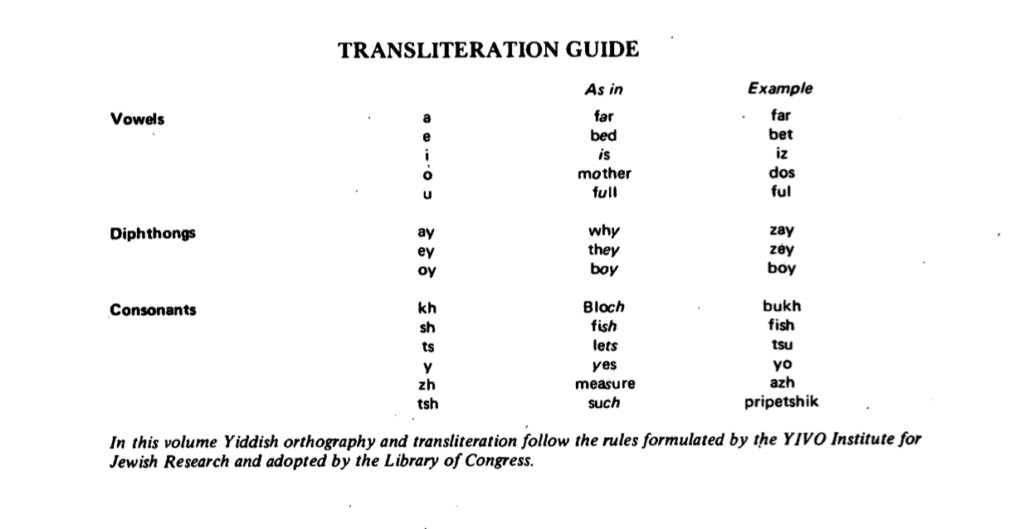

Transliteration is a system of representing the sounds of Yiddish by letters of the Roman alphabet. It has become the lingua franca that connects Yiddish-lovers at various levels of skill in Yiddish: those who are expert in reading, writing, and speaking Yiddish use transliteration to speed up and simplify communication among themselves without having to write cursive Yiddish or type Yiddish with letters of the Hebrew alphabet, which is still a slow, complicated process even with modern computers; those whose ability to read Yiddish in its original alphabet is poor but who understand the language reasonably well become, through the use of transliteration, able to read Yiddish as freely as their more learned colleagues can. They are also able to transmit Yiddish messages of their own quickly and easily. The only basic requirement for using transliteration is knowledge of what the Yiddish words sound like (some words are derived from Hebrew and the sound cannot be readily figured out from the spelling.) Learning the rules of transliteration is simple and quick—anyone can become an expert in half an hour. However, to facilitate mutual understanding we must use a standard transliteration rather than an everyone-for-themselves transliteration, by analogy to the written standard Yiddish (klal-yidish) that is now used in magazines, newspapers, and books by all educated Yiddish-speakers regardless of their individual spoken dialects.

Our aim with these new translations was explicitly not to produce a singable version of the songs in English. We want people to sing them in Yiddish. Rather, with the aim of our users understanding what they are singing, we stayed as close as we could to a line-by-line, literal translation. The result should also be of use to students of Yiddish more generally.

In 1861, M. Berlin, an ethnographer in Russia, commented that synagogue songs are the only songs that Jews know; while at approximately the same time, in 1865, a Russian Jewish historian, I. Orshanski, in discussing the lack of printed data or statistics on Jewish emigration to America, wrote that it is in the Yiddish folk song that evidence of this phenomenon is provided. Work on the first major collection of Yiddish folk songs was started in 1898 by the Jewish historians, Peysakh Marek and Saul Ginzburg, and was published in St. Petersburg in 1901.

At about the same time, in Warsaw, the renowned Yiddish author, I.L. Peretz, and the folklorist, Y.L. Cahan, were collecting folk songs. In Hamburg, Dr. Max Grunwald started to publish the Mitteilungen zur judischen Volkskunde in German, with the participation of Dr. Alfred Landau and other eminent folklorists. Interest in such activity was also stimulated by the St. Petersburg Society for Jewish Folk Music, established in 1908. Members included the composers Yoel Engel, Moses Milner, Joseph Achron, and others. The first Jewish Ethnographic Expedition in 1912, headed by S. Ansky, author of The Dybbuk, also contributed greatly to the interest in Yiddish folklore and folk song.

Following World War I, the collection of Yiddish folk songs was further developed in Kiev and in Minsk, as well as by the Yiddish Scientific Institute (now the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research), at first in Vilna and later in New York, under the direction Dr. Max Weinreich, as well as in Israel. Collectors and correspondents were trained and encouraged by the new centers, and also important studies by scholars on the Yiddish folk song were published. Some of these studies revealed that songs which were thought to be of recent date were actually centuries old and had been part of the Jewish song repertoire even before the settlement of Jews in Slavic countries. These studies pointed out where old and new elements had fused, as had universal and Jewish motifs, religious and secular themes.

Yiddish songs pass like eternal prayers from generation to generation, from the heart to the mind, from the mind to the soul.

Transmitted this way, they bring solace to weary old men and dreamy children—and not only solace, but also delight and love.

Who was the first to sing our song?

The beloved mother who wanted to put the child to sleep?

Or the wanderer who in the hours of dusk longed to illumine his dream with rays of yesteryear?

Perhaps even the Hassid who with his melody at the Sholosh Sudes (third meal) sought to restrain the Sabbath with all his might?

Say “Yiddish Song” and you remember your childhood years.

Say “Yiddish Song” and you feel like singing along with the nostalgic songs like “Oyfn pripetshik,” “Rozhinkes mit mandlen,” “Motele,” and indeed Mordechai Gebirtig’s “Es brent, oy, briderlekh, es brent!”

Religious ecstatic melodies, soulful songs, workers’ songs: It is a garden with many trees, a book with various chapters, a palace with numerous rooms.

From whence does my love for the Yiddish song stem? It is older than my love for music. It is like a treasure in which you find the strings of a timeless violin.

The Yiddish song is the celebration of the Yiddish language—and its obstinate determination to vanquish despair and resignation.